The Day of the Triffids

Without a clock the place simply couldn't work. Each second there's someone consulting it on births, deaths, doses, meals, lights, talking, working, sleeping, resting, visiting, dressing, washing-and hitherto it had decreed that someone should begin to wash and tidy me up at exactly three minutes after 7 A.M. That was one of the best reasons I had for appreciating a private room. In a public ward the messy proceeding would have taken place a whole unnecessary hour earlier. But here, today, clocks of varying reliability were continuing to strike eight in all directions-and still nobody had shown up.

A nasty, empty feeling began to crawl up inside me. It was the same sensation I used to have sometimes as a child when I got to fancying that horrors were lurking in the shadowy corners of the bedroom; when I daren't put a foot out for fear that something should reach from under the bed and grab my ankle; daren't even reach for the switch lest the movement should cause something to leap at me. I had to fight down the feeling, just as I had had to when I was a kid in the dark.

You'll find it in the records that on Tuesday, May 7, the Earth's orbit passed through a cloud of comet debris. You can even believe it, if you like-millions did. Maybe it was so. I can't prove anything either way. II was in no state to see what happened myself; but I do have my own ideas. All that I actually know of the occasion is that I had to spend the evening in my bed listening to eyewitness accounts of what was constantly claimed to be the most remarkable celestial spectacle on record.

And yet, until the thing actually began, nobody had ever heard a word about this supposed comet, or its debris.

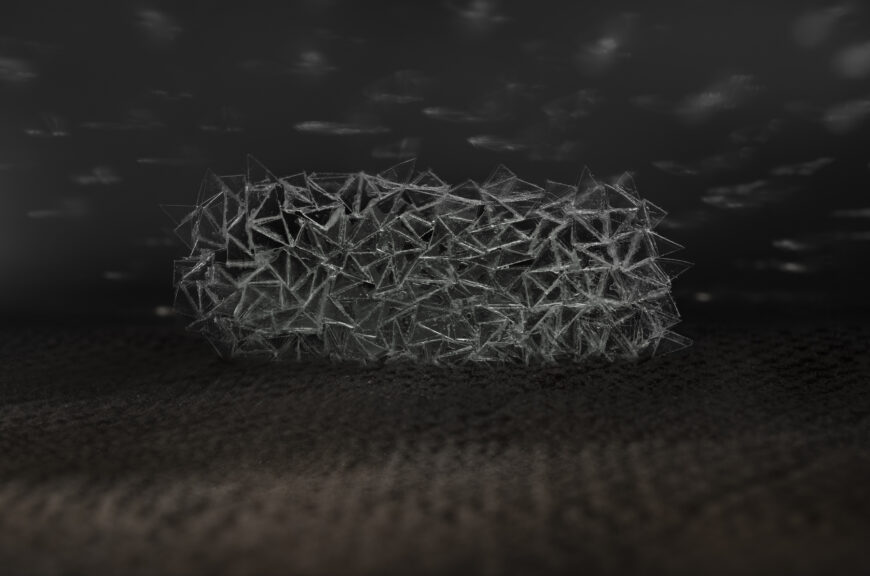

The sun was close to setting. We had knocked off for the day and were looking with a sense of satisfaction at three new fields of nearly fully grown triffids. In those days we didn't simply corral them as we did later. They were arranged across the fields roughly in rows-at least the steel stakes to which each was tethered by a chain were in rows, though the plants themselves had no sense of tidy regimentation. We reckoned that in another month or so we'd be able to start tapping them for juice.

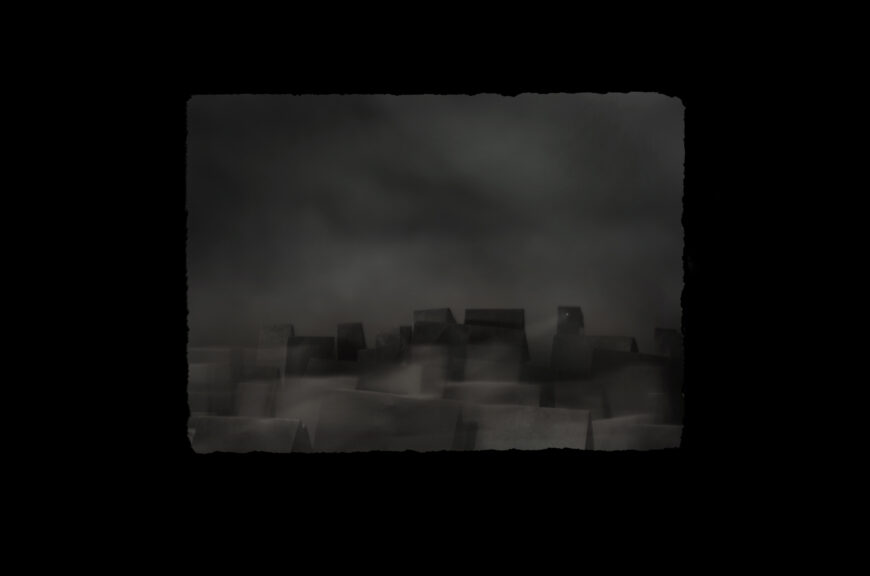

The day was perfect for early summer. The sun poured down from a deep blue sky set with tufts of white woolly clouds. All of it was clean and fresh save for a smear made by a single column of greasy smoke coming from somewhere behind the houses to the north.

I stood there indecisively for a few minutes. Then I turned east, Londonward.

To this day I cannot say quite why. Perhaps it was an instinct to seek familiar places, or the feeling that if there were authority anywhere it must be somewhere in that direction.

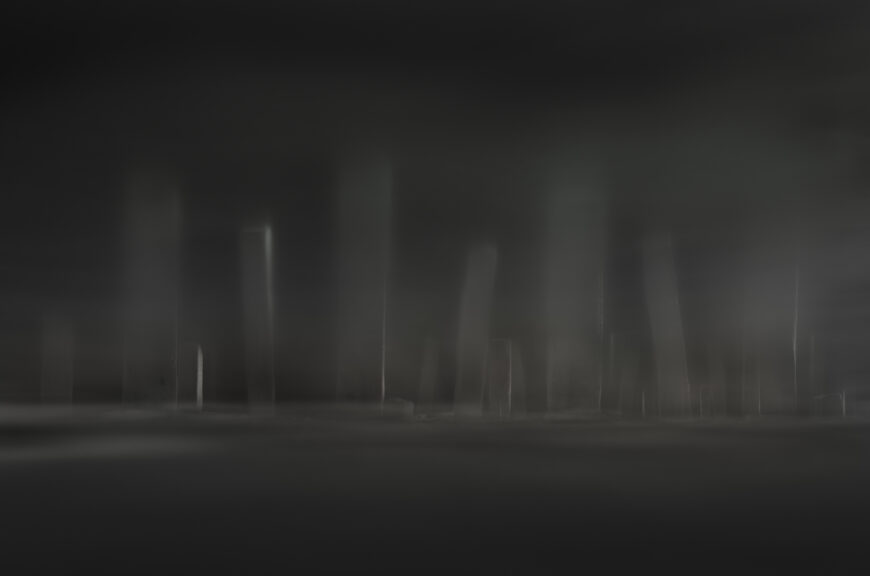

From where I stood I could see them come in single file out of a side street into Shaftesbury Avenue and turn toward the Circus. The second man had his hands on the shoulders of the leader, the third on his, and so on, to the number of twenty-five or thirty. At the conclusion of that song somebody started "Beer, Beer, Glorious Beer!" pitching it in such a high key that it petered out in confusion.

I was stretched in comfort on the edge of sleep when there came a knocking at the door. "Bill," said Josella's voice. "Come quickly. There's a light!"

"What sort of a light?" I inquired, struggling out of bed.

"Outside. Come and look."

She was standing in the passage, wrapped in the sort of garment that could have belonged only to the owner of that remarkable bedroom.

"Good God!" I said nervously.

"Don't be a fool," she said irritably. "Come and look at that light."

A light there certainly was. Looking out of her window toward what I judged to he the northeast, I could see a bright beam like that of a searchlight pointed unwaveringly upward.

"That must mean there's somebody else there who can see," she said.

"It must," I agreed.

I tried to locate the source of it, but in the surrounding darkness I was unable to decide. No great distance away, I was sure, and seeming to start in mid-air-which probably meant that it was mounted on a high building.

At Hungerford we stopped for more food and fuel. The feeling of release continued to mount as we passed through miles of untouched country. It did not seem lonely yet, only sleeping and friendly. Even the sight of occasional little groups of triffids swaying across a field, or of others resting with their roots dug into the soil, held no hostility to spoil my mood. They were, once again, the simple objects of my professional interest.